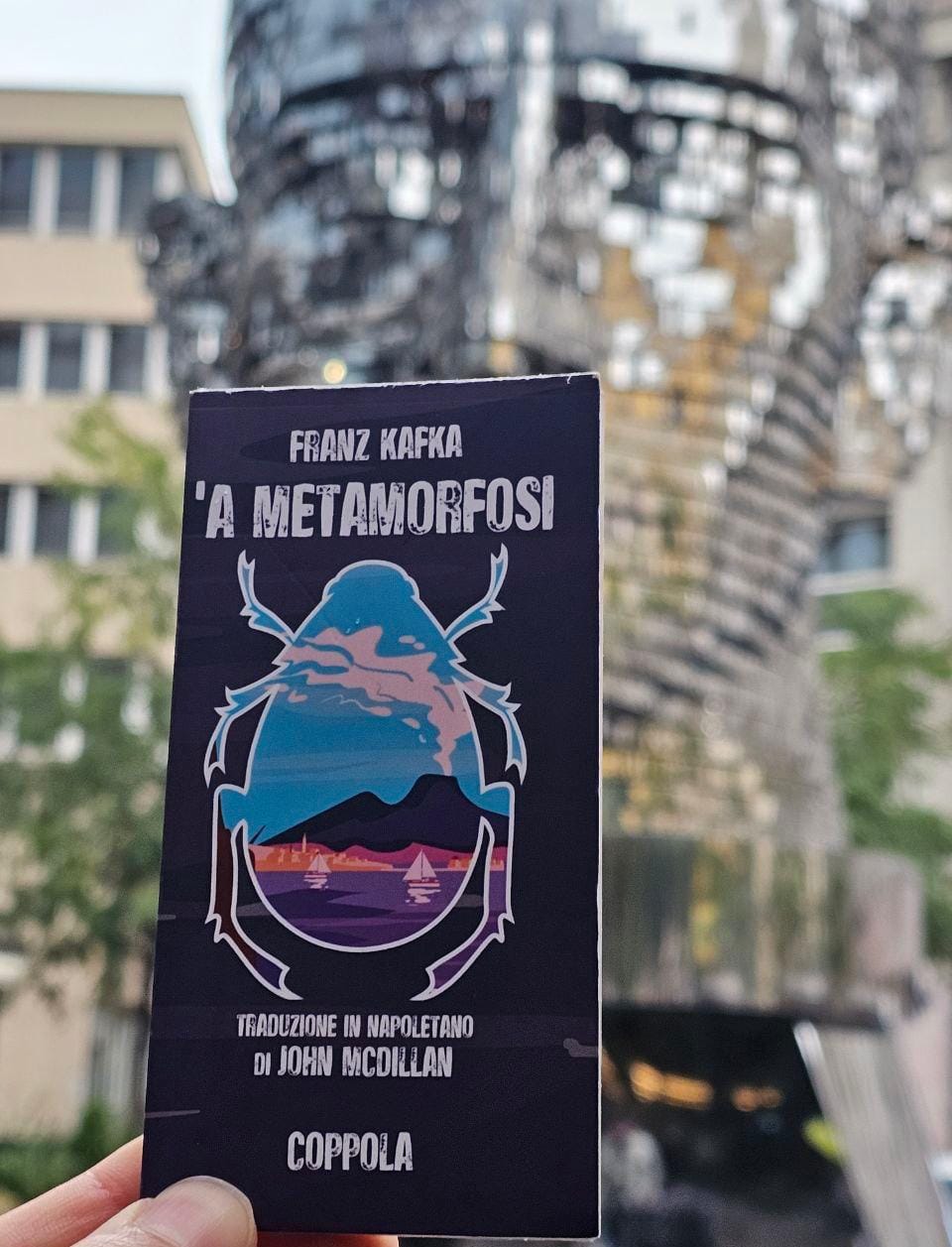

There are books that we will continue to consider masterpieces, capable of overcoming the challenges of time. Likewise, there are languages and dialects that, while crossing centuries, retain their purity and authenticity. When these two dimensions meet, works are born that deserve to be told to future generations. Such is the case with the new work by John McDillan, a pseudonym for a Neapolitan author who translated Kafka’s magnum opus, The Metamorphosis, into Neapolitan dialect.

In this interview, we explore his translation journey, the balance between fidelity to the original text and modernization, and his attempt to bring contemporary readers closer to Kafka through the language of his homeland. McDillan also shares his vision of Bizarrism, a literary movement that embraces the absurd and intersects with his interpretation of Kafka’s masterpiece. A work that is not only a tribute to a great writer, but a cultural bridge for a new generation of readers, who will find in McDillan’s pages a fresh and authentic way to approach literature, rediscovering the value and beauty of their native language.

Neapolitan has often been associated with verse, fairy tales and classical literature. What prompted you to translate a contemporary and complex work like Kafka’s The Metamorphosis into this language?

Personally, I was driven by that healthy desire to show that the use of this language has no limits. Many people believe – mistakenly – that Neapolitan is a dialect to be used exclusively in comedy, but this is not the case. Of course, with Neapolitan you can make a person laugh, but you can also make him cry, reflect, fall in love, encourage and, speaking of Kafka, disturb. By translating a work like “The Metamorphosis,” I wanted to show that the use of Neapolitan is unlimited, because it can cross all the spectres and all the little glimpses of the human soul.

He chose to maintain a certain fidelity to the original but also included modern expressions and vocabulary, which he claims is also inspired by the spread of Neapolitan due to contemporary artists and lyricists. What was the balance between respect for the text and actualization?

It was quite an experimental operation. In my opinion, translating any text into Neapolitan becomes a kind of great compromise: a middle ground between remembering the grammatical tradition and accepting oral recurrence, between going along with the evolution of the current language while showing respect for its basic root…To translate, I started reading what has already been translated into Neapolitan, such as “La Tempesta” translated by Eduardo De Filippo (Einaudi, 1984), ” ‘O Principe Piccerillo” by Roberto D’Ajello (Franco Di Mauro Editore, 2017), just to give two examples. I also drew from essays, such as, for example, “Una Lingua Gentile” by Nicola De Blasi and Francesco Montuori (Cronopio, 2020) and “La Parlata Napoletana,” by Sergio Zazzera (Giannini Editore, 2023).Then I also listened a lot to the songs of Pino Daniele and Liberato; I paid attention to the translations of some English songs sung by the duo Ebbanesis, DADÀ and I also took into consideration the lyrics of Geolier, Nu Genea, Andra Sannino and so on. In short, I did not exclude anyone from being “a teacher,” from opera singer to neo-melodic singer. To finish such a work, I tried to sift through everything currently available in the Neapolitan language. Indeed, this language still survives precisely because of musicians (but also directors, comedians, playwrights and poets). In this regard, I reviewed all of Massimo Troisi’s films, some of Alessandro Siani’s, but without forgetting Eduardo’s timeless comedies.In short, the balance between respect for the text and actualization was there, but nonetheless I took into account the current context and the speech of today’s young (and not so young) people.

In your adaptation, a parallel emerges between Kafka and Eduardo De Filippo, especially in the way he expresses emotions such as anguish and irony. Can you tell us more about this juxtaposition?

Certainly. As I mentioned, the two authors are connected by a thread that can be called “melancholia” or, better said, ” ‘pucundrìa.” They both had that focus on telling about man by highlighting his anxieties, concepts and preconceptions. The juxtaposition was fitting, especially in the dialogues found in “Metamorphosis.” Once the translation was finished, I reread the whole thing: I felt like I was in the theater, sitting in my comfortable armchair waiting for the curtain to open, show the stage with its actors and, in conclusion, slowly close again, leaving me to reflect with a bitter smile on my lips…

He calls himself the progenitor of “Bizarreism.” Tell us more about it.

Indeed. Bizarre was born in 2015. Besides me, there was a cloud of people who started writing following in this wake, especially on some digital platforms. I tried to create a narrative style based on this concept that jumped into my head on a cold December morning: “The greatest nonsense for a nonsense is to make sense… “Writing in this way allows me to be able to give a caress to children and a slap in the face to adults. The world is overflowing with “adults,” whom I identify as “Normaloids”-that is, that multitude of people who do strange things, such as starting wars to promote peace, buying yes medicine to cure themselves, but then smoking whole cartons of cigarettes. Here, Bizarreism tends to defend an increasingly rare minority, that is, the Bizarre, in other words, that individual who has managed to remain a child at heart, despite everything and everyone.Of course, what I write tends to be a truth hidden under beautiful lies — quoting Dante. My goal has always been to leave a mark on readers, even with a reading that apparently makes no sense.A distracted reader will not be able to appreciate what is between the lines, but a reader who is distant from everything that is considered normal for most people will be able to understand every single nuance of what he or she reads. In other words, the best part of Bizarrism is hidden right there, “between the lines” of my texts.The first novel that is the fruit of Bizarrism is “17 Novelle Bizzarre +1,” and the last one scheduled to be released in 2025. It will be published by the Italian publishing house Winter Edizioni, once again under my pseudonym, John McDillan.

How does this literary movement relate to your work on Kafka and your choice to translate a masterpiece like The Metamorphosis?

Kafka taught us to love the absurd. Bizarreism is hinged on the absurd. In other words, there is no trace of magic or real science in my texts. In Kafka’s texts, when a man wakes up as a cockroach, the reader is given no explanation. He woke up as an insect, period. Kafka’s goal is to thrust the reader into an absurd context, which only those with a certain sensibility can understand deep down. For example, I see in the Metamorphosis the difficulty of a family in helping one of its members who becomes, unexpectedly, differently abled.Ultimately, I try to follow the same modus operandi as Kafka. There are not many explanations to give other than free explanations, which each reader can extrapolate from context, feelings and himself…

Your work as a translator seems to be in dialogue with Neapolitan popular culture. Is it also a way to bring young Neapolitan readers closer to Kafka and other authors?

Certainly. I am in full swing just to translate other well-known authors as well. I am reminded of what Gaetano Ceraso (author of a 1903 Neapolitan vocabulary) wrote. He wrote that “he who exactly speaks, exactly writes.” As for me, I believe that he who exactly reads, exactly writes as well. This is why I have started translating several classic works into Neapolitan, precisely to encourage reading in our mother tongue starting with something one already knows.This will produce not only greater awareness of one’s own language, but will help Neapolitans limit the mistakes they make when they try their hand at writing in this idiom. By producing works in Neapolitan (translated, or even original), one contributes to the survival of the language. That’s why, in addition to translation projects, I have in store a quirky novel written entirely in Neapolitan – and then also translated into Italian and other languages to help its dissemination. I’m just waiting for the right publisher so I can publish it, so my dear readers can savor it. And come to think of it now, it is ironic that this novel I am discussing with you (of the New Yorker) was actually set there, where many Italians, as well as Neapolitans, reside: in the heart of beautiful and timeless Manhattan…

The article Interview with John McDillan, translator of “The Metamorphosis” into Neapolitan comes from TheNewyorker.