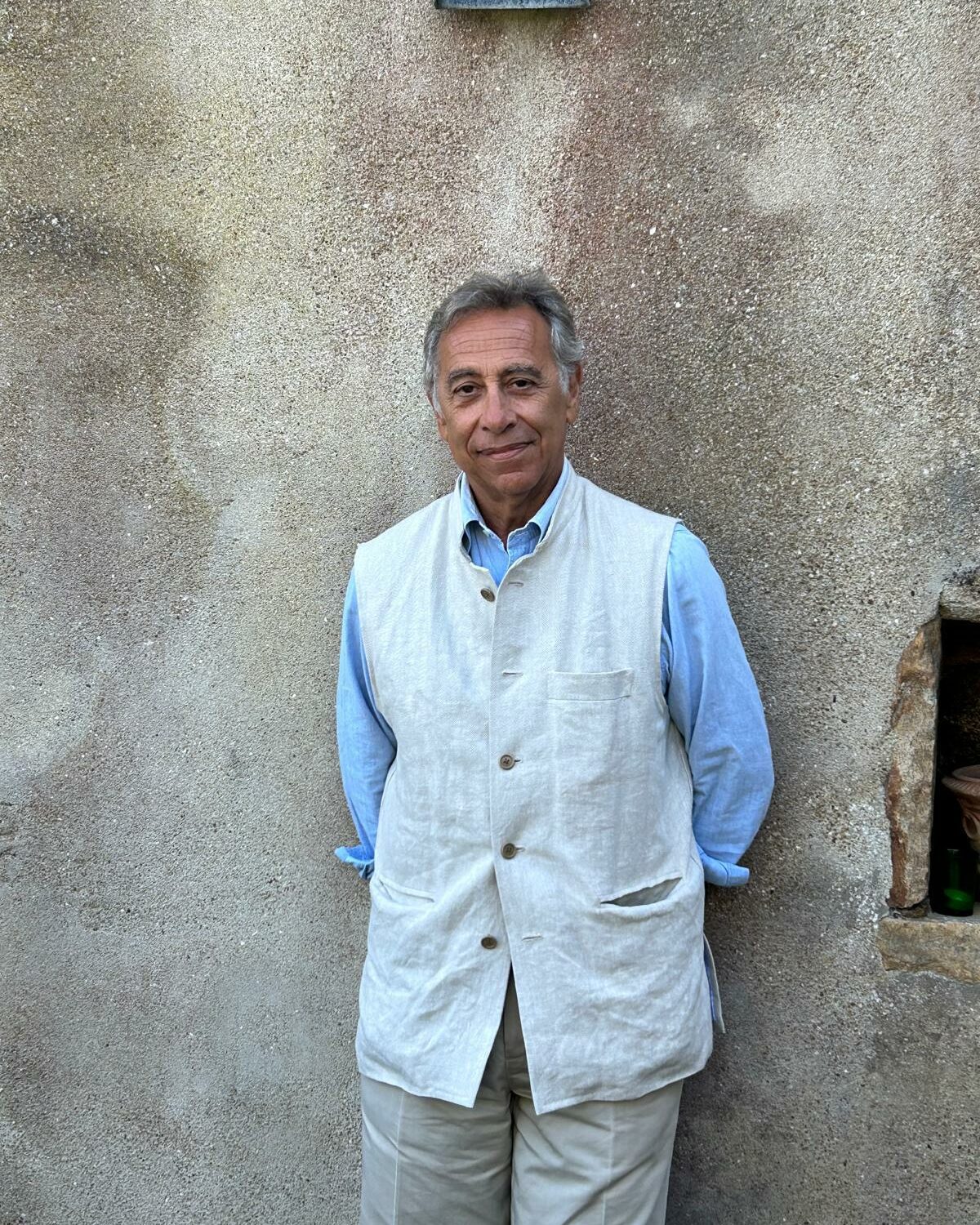

Architect and tireless cultural promoter, Alberto Sifola of San Martino calls his association, Friends Of Naples, a group of volunteer “menders.” Between doorways, medieval chapels and contemporary installations, he recounted their commitment to the maintenance and recovery of a historic-artistic treasure around which a heritage of relationships, arts and crafts revolves. From the city of Naples, to give birth to new forms of virtuous patronage.

Let’s start with the “genesis.” How was the Friends of Naples project born?

The idea was born when I was vice president of the Italian Historic Houses – Campania Section. After some time, together with the president, we felt the need to not simply deal with cultural initiatives, but also to act on the territory. The first intervention was carried out on a doorway from 1467, in the palace of Diomede Carafa in Via San Biagio dei Librai in the heart of Naples. We decided to restore it, and the operation, also financed by private individuals, was successful. The doorway is still there, despite the fact that they continue to daub it causing great pain to our restorer who, however, continues to take care of it by doing maintenance. We are a group of volunteers and, in order to keep it tidy and mending as I often say to make the idea better, we are really willing to do and give so much.

Why “mending?”

Because to do a proper restoration requires a lot of time, huge resources, and a rather well-established collaboration between institutions and private individuals. For the time being, we make the maximum effort with everything we have at our disposal for this mending, in the broad sense of the word.

After this first phase you structured yourselves and it became more and more successful.

After the work on the door of San Biagio dei Librai, I realized that I could not pursue the project as Dimore Storiche Italiane, because its mission is not to deal with restoration. Therefore, we subsequently founded the Friends of Naples association, and it was immediately a success. The City of Naples after some time proposed that we take care of the San Gennaro Gate, the oldest in Naples, which houses Mattia Preti’s last fresco for the city gates. From this proposal, we then started the procedural process with the city administration, FAI and the Superintendency of Cultural Heritage. A great satisfaction.

From that time on, you worked so hard, not even the pandemic stopped the restoration work.

During Covid, we carried out the restoration of Porta San Gennaro with one restorer at a time on the scaffolding to comply with anti-pest rules. It was during that bad period, by a twist of fate, that the original fresco was painted to thank St. Gennaro for ridding the city of the plague. Figures in masks can be seen on the painting carrying away the bodies of the deceased.

I imagine that to do all this you had to build a network of donors involved in the association.

Of course, our work is all about relationships and donors. Porta San Gennaro was donated in large part by ACEN, the Association of Home Builders of Naples, and a private patron. Specifically, the then president of ACEN, Federica Brancaccio, decided to donate all the money that would have been used for traditional Christmas gifts to the restoration of the Gate.

Is your main goal to enhance the artistic heritage of the city of Naples?

Absolutely, with maximum effort we try our best to bring to light and maintain the wonders of our city. We have to consider all the stumbling blocks we find in our way. We are in a historical period of great projects: the great project of Palazzo Fuga, the museum, the subway lines, and we are overjoyed. But suffice it to say that the metro stations also need maintenance. For example, with another intervention of ours, we cleaned up some sculptures in Materdei station. We are often engaged in fighting the belief that the more you put off routine maintenance, the more you save. Instead, it is exactly the opposite. The earlier you intervene, the more you save. The further you go, the more the amount of money for restoration goes up, and above all, pieces are lost. A reversal of this trend is needed.

Your success has also come to artists who have chosen to make donations.

The Tropico singer gave us a bonus on every ticket he sold for the concert he held in Naples. He sought us out. He was impressed after seeing a restoration that is still ongoing on terracotta statues that are in the church of Sant’Anna dei Lombardi, dating back to 1490 and made by Guido Mazzoni.

Are local restorers involved in your work?

A central aspect of our mission is precisely to provide jobs for our excellence. We always strive to enhance our artisans, and that is mainly why we have never stopped and found ways to keep going even during the pandemic. Our artisans are very fine, very good. They are able to do things that it is difficult to see done with such proficiency elsewhere. In my opinion, it is incumbent on the citizens to lend a hand and make a real contribution to the historic Neapolitan crafts. We want our craftsmen to work, to be happy, and we want their passion not to be frustrated, so that they can pass on their art to their children.

From the perspective of relations with institutions on the ground, what is the biggest success so far?

We are very happy that the Superintendency in some way takes us into consideration and does what it can to always help us out, perhaps even quickly initiating emergency procedures through their officials whenever we needed them.

What is your greatest wish for the near future?

The wish is to overcome that way of thinking that if one does something, the other has to tear it down just because he did not do it. Instead, it is much nicer to see everyone moving together and donations coming in even from abroad. I would also like to raise awareness among Neapolitan emigrants and their descendants, I would like to bring on board all the pizza makers from New York who came from Naples and so on. I would like to start first of all with those who do the simplest jobs, because the art historian is certainly easier to raise awareness. I would like someone to come from somewhere in the world and say, “I’m Neapolitan, my grandparents left from Immacolatella and I want to donate to recover the artistic heritage of my ancestors.” It is not impossible, it has already happened once. With twenty small donors from abroad, we put in place a fresco or what the donors themselves choose to recover.

The article Alberto Sifola of St. Martin, the art of “mending” beauty comes from TheNewyorker.