United States and Italy are linked by a long history. One of these concerns the spread of Protestantism in our nation, both by the hand of Italian emigrants, converted to America and then returned, and thanks to a mission of evangelization that for almost a century brought in Italy another conception (not opposite but complementary) of the Christian message.

In an essay by Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, entitled “Kafka, for a minor literature”, the two authors supported the greatness of the minor narrative (yellow, science fiction…). You can use the same criteria for the history of Protestant Christianity in Italy.

We are talking about “Between mission and union, the 150 years of the Baptist Church of Teatro Valle (1875-2025)”, a broad and documented text, the work of Martin Ibarra Pérez, theologian, historian and Baptist pastor who formed in the native Spain, and then in Switzerland and England. The importance of the volume is demonstrated by the venue of the presentation, the Sala della Lupa, the most important of Montecitorio after the Chamber of Deputies. The meeting was attended – among others – the vice-president of the Chamber on Sergio Costa, the president of the Ucebi Sandro Spanu, the author Martin Ibarra Pérez, the pastor of Teatro Valle Simone Caccamo, the honourable Raffaele Bruno, a baptist congressman.

The Baptists were part of the events of post-resorgimental Italy: For example, the coat of arms of the Italian Republic, with the star and a crown of olive and oak, is the work of Paolo Paschetto, an important baptist exponent (the father was a shepherd and professor of valdes), painter and artist (in addition to the coat of arms of the Republic, in 1907 he also won the graphic design for the five lire bill, he made the windows of the Casbalina of Villa Torlonia, decorated that part of the Italian Pavilion of Piarriste.

The history of the Baptist Mission in Italy began in the aftermath of Unity, a period in which political and religious power were separated as never before, which then was what asked the same Messiah: “Give Caesar what is of Caesar and God what is of God.” It passed from the “Papa-re” to an openness to secularism and pluralism sabaudo: in Piedmont the Waldensian community, anticipator of the Lutheran Protestant, after centuries of repression in 1848 had become free to profess its cult thanks to Carlo Alberto di Savoia.

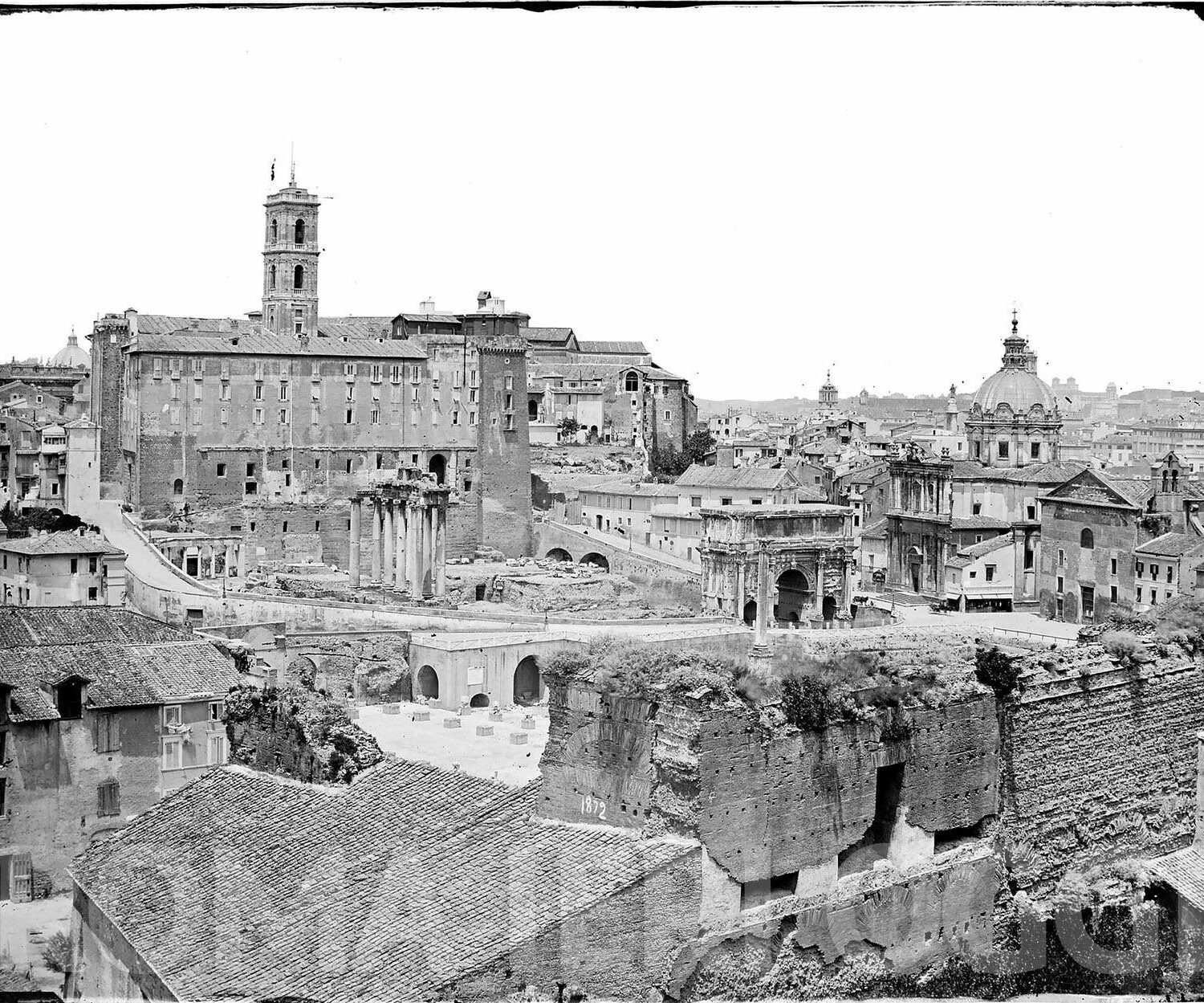

Not by chance, the first English missionaries arrived in Italy in 1863. The relationship between Risorgimento Italy and the United Kingdom – born with the Grand Tour, which gave a great impetus to arts and History throughout Europe – developed thanks to the support of the United Kingdom to the independence of Italy and Greece. It was important, in this framework of political, cultural and religious sympathies, the role played by Giuseppe Mazzini in his London exile.

The first missionary, Edward Clarke, settled in 1866 in La Spezia, where he founded the Mission. The second, James Wall, set the headquarters of the Baptist Missionary Society in Bologna in 1871. Also in 1871 – a year after the Breccia di Porta Pia – arrived in Italy Wolfred N. Cote, the first American missionary of the South Convention, to which he added two years after G.B. Taylor, always sent by the South Baptist Convention, the one from which came Martin Luther King, the pastor who gave victory to the movement for the rights of the black population.

The Baptist work is the fruit of the Protestant Resveglio, which since the 17th century had formed new ecclesial forms almost continuously. Among the first and most important are the Methodism of John Wesley and Pietism, to which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Immanuel Kant (see his “Religion within the limits of the Reason alone”). The father of pietism was Philipp Jacob Spener, who in Frankfurt am Main founded the “Colgia pietatis”, private assemblies that gathered in houses – and not in churches – for prayer cults and to study biblical texts. It was a return to the practice of the primitive church, which separated both from Lutheranism and from those forms that – according to Protestantism – have grafted a “ paganism” that in fact is not present in the Bible (the cult of saints, the Marian one, the one of the relics).

Clearly, pietism, so disruptive for all Christian confessions, found obstacles even in Lutheranism. However, his anti-conformism brought doubts about the principle of the delegation of faith to the Churches intended as an institution, and the dissociation from prescriptions to blindly obey.

Lo stemma della Repubblica Italiana, disegnato da Paolo Paschetto, artista protestante e figura centrale del battismo italiano del primo Novecento.

Is there an awareness of the differences between good and evil, justice and injustice, love and hatred? If yes, it lives in consciousness, that is, in the “science with…” that is, that Esther which allows us a continuous reconstruction of our actions in the world and a rational “critical of pure reason” thanks to the Christian message. “Love your neighbor” (“prossimo” in Hebrew king’a (ר eעo) and also means companion, spouse, friend) is a commandment closely related to “Love your God”, the next Christian, that is, Jesus. That is, you cannot really love the other, if you do not love God first. St. Paul writes “Faith is certainty of things that hope, demonstration of things that are not seen”, while non-faith is based on the certainty of the things that are seen. However, for at least one hundred years science and science meet. For the first time we are faced with a reality in which res extensa and res cogitans are united and -perhaps – tied to a res universalis inafferrabile for computation and classical logic.

Currently the population of the Italian Baptist churches reaches 14 thousand people, but for some time there is a sharing with the Valdese and Methodist churches, which brings Protestantism to better numbers, even if contained. The difficult spread of Protestantism in Italy has several causes: the first is that “the missionaries were bearers of theological and cultural instances that emerged and evolved in their countries of origin”, as Ibarra Pérez writes, specifying that the Italian context is different from each other, because of the Vatican. Moreover, the hostility of the Catholic Church, already affected by the loss of temporal power, was translated into a “small persecution”, when the numbers of Protestants began to grow. Many communities were already born thanks to the Italian emigrants in the Americas, where they came into contact with a Christianity less delegated to priests and less prescribed. Returning to Italy, peasants and workers “engaged” relatives and compaesani. This factor led to the birth of rural and southern communities, where emigration was more marked.

The Anglo-American missions took advantage of the co-operation of the strikers, a figure whose work (paid, from missions) consisted of the distribution of leaflets, leaflets and small editions of the New Testament. The same did the faithful of the communities, especially in the cities. I remember an old man from Naples, who every day placed a chair in a street of the Rione Materdei, to distribute to the passing booklets printed by the Baptist missions. I also remember a Mexican boy (on 18 years), with whom I spent a few hours discussing religion on the train between Mexico City and Merida (Yucatan). At some point he went down because his ticket stopped a hundred kilometers after Vera Cruz. But after ten minutes, by train departed, you rividi: he had asked for a few peeps in alms to prolong the journey and thus continue the discussion.

In just unified Italy, “the American Mission used five strikers, while the British Mission reached ten in the four areas where it divided its work: North, Center, Rome and South Italy”. When a small community was formed in a country or neighbourhood, the mission sent a pastor, who provided a home and a small salary.

“These groups rose in the midst of deep hostility by Catholic fellow citizens, while they were seen with sympathy by the anti-clerical liberals and Masons. This was translated into violent actions… “Like that of Barletta, where in an unprotected populated riot directed by two priests some evangelicals were killed (1866)”, adds Ibarra Pérez.

I confirm that the phenomenon was widespread: My maternal family had an evangelical pastor, who at the end of the 1920s was sent with wife and children to a Sicilian city. After a few months of the boys began to throw stones to him (an aunt told me “they were trying to stone him”). He changed his way every time, so he managed to move on for a couple of months. Then the carabinieri called him and told him to leave as soon as possible, because someone wanted him dead. From the evening to the morning he fled to a city 100 kilometers away, with suitcases and the whole family. The violence therefore were not of little importance (see infra).

A growth factor – at the beginning of the ‘900- was the communication, starting from the Claudiana publishing house in Turin. They formed important magazines such as The Witness, The Parent and especially Bilychnis, whose editing also produced the weekly Conscientia. This also reached the population of the city: professionals, employees, workers, even those who were not interested in Christianity. Giuseppe Gangale wrote that the Italian nation, deprived of the Reform, with the spread of the evangelical Protestantism would have overcome historical difficulties, also caused by the pervasiveness of the partycracy and by inclinations to totalitarianism. Conscientia was closed by fascism in 1927. The growth – however slow – of the evangelical and Baptist communities led in 1901 to the creation -in via del Teatro Valle – of a Baptist Theological School for the formation of the new shepherds, then it is confluent in the Waldensian Faculty of theology of Rome.

In 1907 the pope had expressed a condemnation of the Modernist movement, considered “foreign” to Catholicism where he was born. The two Baptist missions seemed appropriate to reorganize, taking advantage of the Catholic crisis. “The British had given the Americans all their communities to the south and in return they had the responsibility of all the communities of Piedmont.” In 1902 the UCAB, which federated the Italian churches, remained under the leadership of the two missions, gained more autonomy. Soon the two missions would be reduced to one, the American one, because the English one had too low numbers and donations. On the contrary, the collection of the faithful of the American churches grew, except to collapse (like the local ones) during the two World Wars and the Crisis of 1929. The missionaries were very surprised that in Spain, Asia, Africa and Latin America the donations of the American faithful cost half compared to Italy, but producing double of the faithful. In order to justify the increase of the requests, moved during the annual reports, they had to explain the great difficulty in finding premises for rent, because of the brakes placed by the Catholic clergy. At that point the Baptists began to buy locals throughout Italy. Only then were there the obstacles of bureaucracy, another monster unknown to the Americans and English, whose missionaries explained to the overseas faithful that “Only who was in China and Italy is able to know the chains of bureaucracy”. The numbers were relocated: “The American Mission in Italy had reached 39 churches and 94 diaspores in 1910 [small churches linked to the greatest, ed], 16 of which opened that year. The total number of church members was 1017.

Colportori protestanti in Italia all’inizio del Novecento, figure centrali nella diffusione del battismo e dell’evangelismo attraverso opuscoli e Nuovi Testamenti.

The First World War for Baptist Churches was a disaster. Some pastors ended up in the front (two of whom died), despite being equivalent to the Catholic clergy. The British mission did not come any further from London. The Americans were charged with everything, but the communities of Venice, Rimini, Cuneo and Novara were closed in the north. The Theological School of Rome was closed for lack of funds and because the members and teachers were at the front, except the American missionary Whittinghill.

In 1915 in the Abruzzi (Marsica) a sisma caused the death of more than thirty thousand people, nine thousand in the Avezzano alone. A nursing mission went to the area, where there was also a small church. To the south, however, three new churches were opened in 1916. In 1917 the defeat of Caporetto provoked a flight of refugees, which ended especially in Milan. In reaction, US President Wilson decided to help Europeans. Twelve Soldier Houses were opened in several cities, which recorded the presence of 157,000 soldiers and officers, to which 60,000 New Testaments and Baptist magazines were distributed.

Un orfanotrofio per i figli dei caduti della Grande Guerra, tra le iniziative assistenziali promosse dalle chiese battiste nel primo dopoguerra.

New Testaments and pamphlets with Bible phrases were distributed to soldiers leaving for the carnage. A special collection in the state of Virginia allowed Christmas gifts to a small part of the troops. After the First World War, in 2023 the U.S. mission and the Baptist churches bought in the Roman district of Monte Mario a plot of 15 hectares that included some buildings then used to house orphans of Caduti in the Great War. The orphanage was dedicated to the memory of the missionary G.B. Taylor. The site would also house the Biblical School, then merged into the Theological Faculty of the Valdese (see Rai documentary). Unfortunately in 1934 the missionary leader of the American mission was summoned by the Ministry of Interior, which demanded a forcing sale of the property (pena l’esproprio), at a price much lower than due. It had to become the headquarters of Opera Balilla. After the sale imposed by the regime, the orphanage was transferred to the district of Centocelle, in a smaller property.

The need to be of help to others, especially to young people, is a constant of Protestant churches. The municipality of La Spezia in 2016 has named a road to the English missionary Edward Clarke (1820-1912). Clarke arrived in La Spezia in 1866. After a few years the mission of La Spezia had a place of worship, a library for sailors, and a small school, in addition to the apartment of the pastor of the church. The school was free and open to those -children and non-who remained without education. In 1887, in Marola, Clarke inaugurated the female orphanage “Victoria Adelaide”, which also hosted dozens of orphaned girls due to the cholera epidemic of 1884. At the end of his life Clarke had founded 23 churches throughout northern Italy, receiving honorary citizenship from the Ligurian Municipality for merits in education.

“In 1882 the encouraging news came from Venice where, (…) despite the persecutions, the church sustained its own expenses and indeed helped the brothers in difficulty for the clerical boycott. Pastor Volpi followed a group in Gioia del Colle, but some of the faithful were wounded by violent people, driven by priests, and Volpi himself was threatened with death if he returned to the town. ”

Previously a qualitative leap occurred in Calitri in Campania in 1906, after a rain of ashes of Vesuvius: the phenomenon was attributed to the presence of Protestants and their propaganda. Writes Martin Ibarra Pérez: “The first sassaioles struck the local and those who attended it, but on 14 April 1906 he prepared an ambush in full rule against the Pastor Creanza, who was expected for worship. He had to arrive in a carriage and the brothers noted the presence of people already involved in episodes of intolerance against the community, which obviously expected the arrival of the pastor. They were able to warn in time the Carabinieri brigadier who intervened with readiness by escorting the Creativity. Since then the persecution has grown to make necessary the protection of the community and the new pastor, so much so that in 1907 the intervention of the army was necessary… [Only] in 1910 the waters returned to water.

In 1909 the attacks struck the communities of Noto and Floridia.

I Italian soldiers during World War I received New Testaments and leaflets distributed by Baptist missions

“The pastor Fasulo had written a booklet in which he questioned the veracity of certain events concerning St. Corrado, a saint who was venerated locally (…). These historical statements were not “graded” by the local bishop, pious women or members of the confraternities. The result was a terrible persecution, with the destruction of the premises of the two churches, the fire of furniture and furnishings, books. The church members were saved thanks to the intervention of the army that mobilized three hundred soldiers to calm the souls. No one was arrested, Pastor Fasulo was invited by the authority to look for other places of residence to avoid other evils. In a sassaiola after the attacks, the pastor’s son-in-law and two sisters of the community were seriously injured. The violence against the evangelicals provoked a small exodus and the return to Catholicism of the most fearful. In Floridia he was the student Chiminelli, a former priest, who suffered the ires of a crowd of three thousand people. The authorities sent troops from Syracuse to calm the agitation.”.

Other attacks on “Avezzano, Altamura, Gravina and other areas of Irpinia and Murgia Bari; the shepherds of Avellino and Matera were assaulted by clericals who armed with sticks tried a lynching, prevented by the intervention of neighbors and friends of the malcapitates”.

The persecutions in Bisaccia continued for years. “The church had to be protected by the military, Pastor Berio had been forced to abandon the city under threat of death, missionary Stuart and pastor Palmieri had been wounded by the launch of stones, despite the protection of a company of soldiers arrived from Avellino.”.

In 1924 a group of young fascists attacked the pastor of Paganico Sabina, Daniele Battisti: “…they assaulted the house where she was. Committed out he was beaten to blood and abandoned in the street, after shooting [in the air] with the riots threatening him to death if he returned to the country” (Cronaca de “Il Testimonio”). Concordat fascism pushed many Protestants to join left or liberal positions such as Justice and Freedom and Action Party as well as the Social-Communist Front).

The peace between the State and the Church will culminate in 1929 with the signing of the Lateran Pacts. At that point he doubled the control and repression of the Protestant Missionary Work in Italy, resumed the violence, both in the “traditional” ways of the sassate, and with plagues and destruction. The social boycott was added to this: the refusal to rent premises for worship, so it was mandatory to buy them at high price from the few willing to sell. Not to mention hostilities in public schools and those in the world of work. “Before 1930 there were many pastors under police control, whose cards are found today in the Central State Archives. In addition to the Saccomani, the pastor D’Alessandro di Formia, Agostino Biagi and Vincenzo Melodia, who had distinguished themselves in the past for their socialist and anarcho-syndicalist militancy. The attention of the police was also addressed to the youth organizations of the evangelical churches. ”

The reconstruction of Ibarra Pérez is very useful to read History at an unconformed point of view but linked to facts. It is also the story of an important church of the Italian Protestant, located in the historical center of Rome, rich in art, home to an incredible work of faith and (so) material help, brought to all without distinction.

Today, when the Italian Baptist Union (Ucebi) has become completely autonomous by missionary presence. Christianity needs new momentum, suffocated by indifference and ignorance. Great changes however there were: no one today is persecuted for religious causes. Faith is more free and less prescribed and impostive. All Christians cooperate with each other. Finally, I would like to recall at least one distinctive feature of Christianity, which is not (in fact) of other religions or philosophies or policies:

Per le culture totalitarie tutti sono colpevoli (potenzialmente, vedi la procedura giudiziaria in Italia);

Per la sottocultura del Politicamente corretto, per gli agnostici indifferenti o menefreghisti nessuno è colpevole. Ne consegue che -nei fatti- di fronte a crimini efferati -soprattutto se commessi da parti avverse- si ritorna al giustizialismo a prescindere;

Per il cristianesimo in itinere, non preconfezionato, e che non sia uno specchio di vanagloria per il fedele, nessuno è innocente (tranne il Messia);

Ma – se nessuno è innocente – tutti dovrebbero responsabilizzarsi e nessuno essere colpevolizzato a prescindere. Ognuno dovrebbe collaborare con la propria coscienza per costruirsi una mappa del territorio che conduce al Bene.

Article The short story of the beaters in Italy comes from IlNewyorkese.