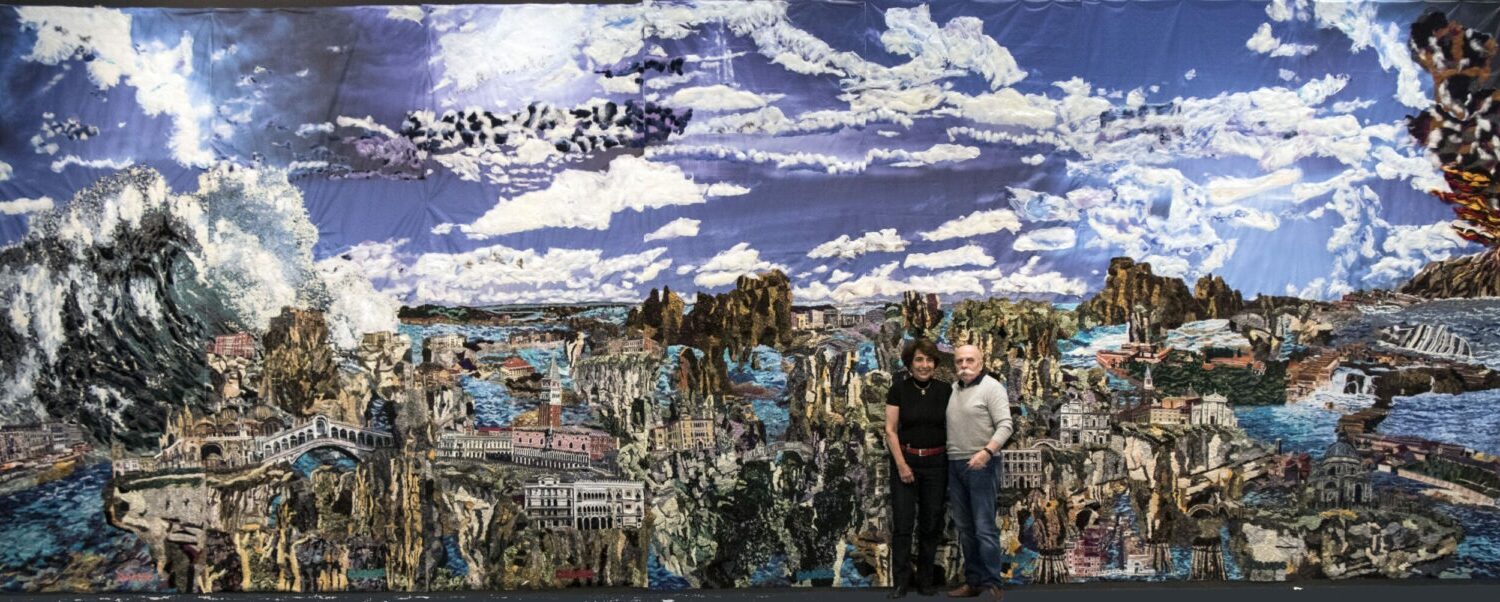

A new form of expression in pictorial art has emerged in Italy. Although only partially similar to the tapestry technique in that it uses colored plant fibers, this art form is distinguished by the arrangement of the fibers on different levels. Photographs fail to capture the visual impact of the work of Daniela Arnoldi and Marco Sarzi-Sartori (known as DAMSS), husband and wife, she an engineer and he an architect, whose knowledge of materials comes from decades of professional experience.

Today, having closed the game with a drafting machine and calculating structures, their four-handed works amaze visitors to their exhibitions, hosted in Italy, Europe and overseas.

“We believe in work that is a challenge for us on the level of creativity, manual skill and technical research. We believed in the synergy of our heads, hands, intentions. Working in two yields more than double; it is a path of continuous refinement,” the two artists say.

La Complessità della “Tessitura”

The technique of “weaving” is complicated for the unskilled. DAMSS’s works also require considerable physical exertion, not only because of their size (“The Last Supper,” inspired by Leonardo da Vinci, measures 8.80 x 2.50 meters, while “The Five Lands” is 21 meters x 2.5 meters long), but also because of the process involving warp and weft. “Weaving” takes time and commitment. Interestingly, “weave” and “text” share the same etymology. The “medium” through which art is expressed varies: in literature it is the word, for painters it is the palette, while in the case of DAMSS the fabrics themselves become the content and message of their works.

Instead of brushes and paints, DAMSS’s textile painting uses recycled fibers from industrial waste. Textile art and the textile trade have historically been an asset for Italy, particularly in Milan, where Arnoldi and Sarzi-Sartori live. Here, fabric becomes “tactile architecture” in three dimensions. “Fiber-art” is an art as modern as it is ancient, recalling the idea that space is curved, as suggested by Albert Einstein’s Relativity.

Moving in this direction are the panels in the “Future Cities” series with “Milan 3000,” “Venice 3000” and “Rome 3000,” each measuring 12 meters by 4 meters in height. These works are visual narratives that reconstruct the three cities a thousand years from now in a science fiction and horror form, similar to the works of Hieronymus Bosch or films such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, as well as the works of Salvador Dali. At the same time, these works echo the news: apocalyptic wars, disasters and the loss of civilization.

L’Intervista con DAMSS

Below is the interview conducted with Arnoldi and Sarzi-Sartori. The reader can imagine a conversation in which the two artists respond almost in unison, providing a unified answer to our questions.

How have you described your “Future Cities”? “In ‘Venice 3000’ we imagine a tidal wave, caused by a new volcano in the Balkan Fault, destroying the lagoon, leaving only ruined monuments, such as San Marco, in a semi-desert environment. In the ‘Inferno 3000’ project, which closes our work dedicated to the hazards of the future, we created a kind of film printed on cotton and other fibers, describing a megalopolis of four billion people, a science fiction tale that reminds us why horror is so beloved by young people. At the same time, there is hope in the escape to other planets–‘Space is the place,’ as the jazzman Sun Ra used to recite.”

Daniela: “One can better understand today’s reality with a representation of the future. Even when we worked as professionals we made art, but I had the realism of an engineer who creates projects, while Marco, as an architect, was more instinctive and did not finish his works. He did not want to finish them because ‘when a work is finished it no longer belongs to me.’ Even then I was attracted to textile art that was not really classical.”

Marco: “I, actually, was the one who wanted to respect the canons anyway: the Vitruvian man, verticality, the golden section. So we combined our experiences, starting with quilting, a way of patchwork that Daniela was working on. Quilting is very much related to the American tradition, to the Amish people who are between Pennsylvania and Ohio. We made several in the first four years of art work together. In quilt technique, precision is key. For us, however, it was still craftsmanship, and it was tight for us. So we found a different form of expression.”

“We have two levels of creativity: the first involves making a shared and defined graphic design, on a scale of 1:100. Then we have it printed to natural size, for example 12 by 4 meters. At that point, the design is silkscreened on several rolls of one and a half meters each. From this draft, we move on to the second phase in textile form.”

How does it relate to tapestries? “The two forms are different. For example, tapestry is created on a loom, it is a weaving, while ours is a stitching. Many people, at first glance, consider fiber art to be a modern version of tapestry, but we sew integrally and without adhesives. We use a non-weaving loom, which we built ourselves. On that we place the panel of fabric that the stitcher works. The fabric stays stretched like a scroll between two rollers that run vertically and horizontally. Our work is not craft: the artist explores the unknown, while the craftsman creates work that can be reproduced in series. Sometimes we have created multiples, for example ‘statues’ with our faces, covered with the clothes we make. This is a tribute to the history of the Italian textile industry and our fashion, expressed with a seriality similar to Andy Warhol’s pop.”

In Warhol’s series there is a chain of differences and reproductions… “We create something like a musical work, divided into movements. For example, in the series on myth or the Cinque Terre series, composed of different parts that, when joined together, form a 21-meter work. To reproduce these works photographically is very difficult: our Fiber art is almost in antithesis with photography, both in terms of size and shades of color. The fiber ‘comes out’ of the plane, creating a three-dimensional effect that the photo cannot render, except partially. Fiber art is matter and color emerging from the flat surface of a canvas.”

Is the material you use expensive? “Fortunately, we have some sponsors, such as Aurifil of Saronno, who donated three tons of yarn that can no longer be used for textiles.”

Does your technique recall digital pixels and 3D in any way? “We use two threads that can alternate top and bottom on the base of the panel, and we paint the details with yarn on the fabric. We use digital for the initial design; our pixels are like a mosaic or wood inlay. We don’t have the canvas, but two layers: above the screen print of the design is the fabric that forms the base, and on the fabric we apply the yarn with which we paint the details. We trace the weft, warp and colors with the threads. We tend to paint like the Impressionists: the work should be observed from a distance, to catch the whole of the stitches and colors. It’s a principle that inspired us.”

“Using matter and not oil paints, the end result is visual and tactile, and creates a dialogue with space that approaches the contemporary. Our works are site-specific art installations.”

What’s next for you? “We have shifted to creating art spaces, so we will continue to work at this level. We have an exhibition planned in Milan, within a new urban regeneration project in Sesto San Giovanni, which will create a new Milan. We are not closing ourselves off to small galleries. But we dream of art that is a monument of nature and culture.”

The article A New Form of Pictorial Art: Interview with Daniela Arnoldi and Marco Sarzi-Sartori (DAMSS) comes from TheNewyorkese.